Divinity Returns in the Messiah

In the second temple period, we find the theme which I have come, in recent years, to regard as the major clue to all the early Christian accounts of God’s action in Jesus.

At the end of the Book of Ezekiel, the temple is rebuilt; the divine glory returns. Click To TweetEzekiel tells of the divine glory, riding on the throne-chariot, abandoning the temple to its fate because of the persistent idolatry of people and priests alike. But in the final dream-like sequence of the book the temple is rebuilt, and in chapter 43, the divine glory returns at last.

This is the point, as well, of the whole poem of Isaiah 40–55: The watchmen will see the divine glory returning to Zion, though when they look closely what they will see is the figure of the Servant.

The point is this: In two of the major so-called post-exilic books, Zechariah and Malachi, the Temple has been rebuilt, but the promise of YHWH’s glorious return remains unfulfilled.

The prophets insist that the Spirit will return, but that it hasn’t happened.

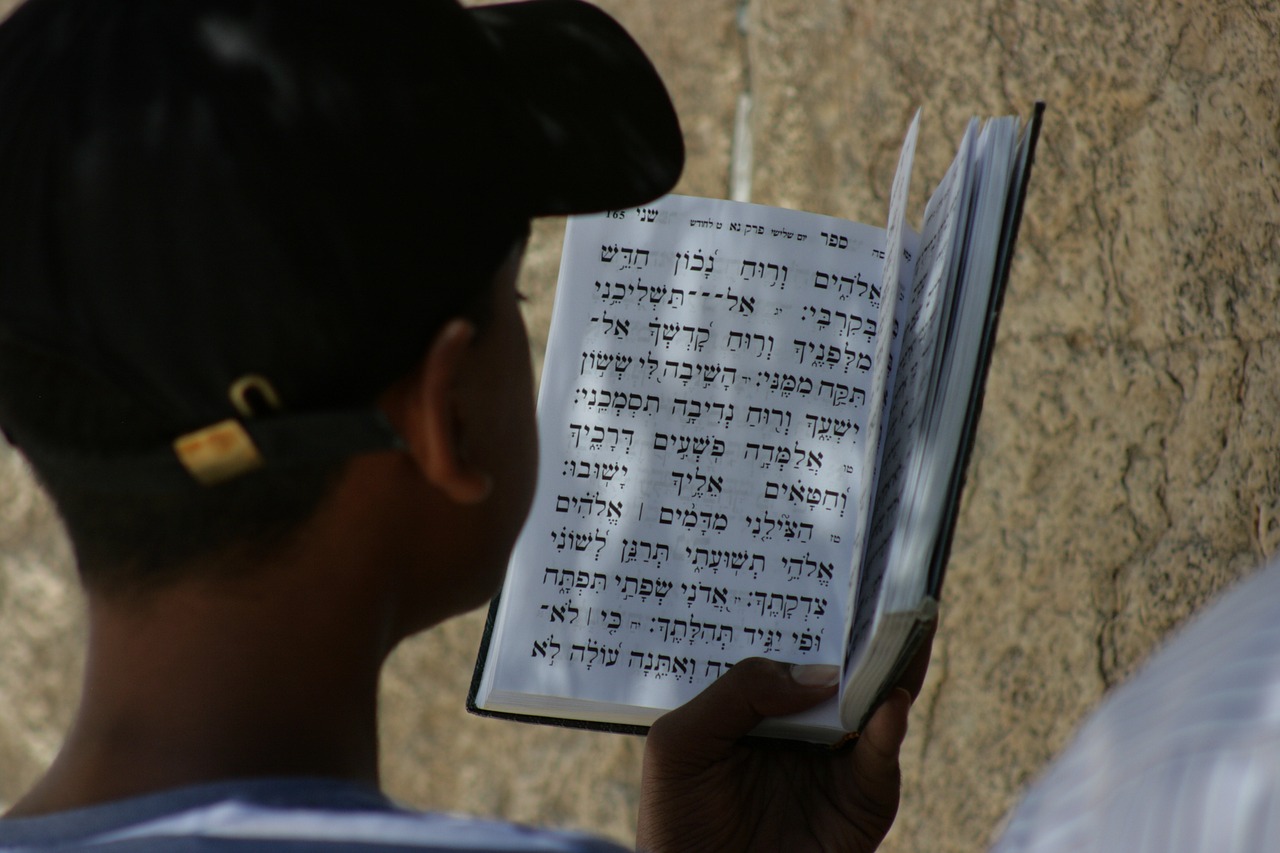

YHWH will indeed return, but that very insistence is powerful evidence that he hasn’t done so yet. Of course the people are offering sacrifice and praying in the newly restored temple, because that’s how sacred space works, as with the Western Wall in Jerusalem to this day, where devout Jews and even visiting presidents go to pray even though no Jew supposes that Israel’s God is really in full and glorious residence on the old Temple Mount.

But when the later rabbis make a list of things that Solomon’s temple had which the second temple didn’t have, they include the Shekinah, the glorious divine presence. The whole New Testament, Mark as well as John, Luke and Paul alike, insist that this is how we are to see Jesus, as the living embodiment of the returning, living God of Israel.

Understanding a the Messiah in Second-Temple Theology

The place to start if we are to understand New Testament Christology, I suggest, is with the second-temple narratives in which Israel’s God had made promises about the new temple, which I have said before, is obviously the sign and means of new creation, with the way in which the logic of that temple-discourse works in terms of the simultaneity of the returning divine glory and the appearing of the true divine image.

The coming of God and the appearance of the truly human one seem to be literally made for each other. These are the themes which harmonize in the music which is the food of love. Those whose ears can only hear one note at a time will find it strange to be told that all these notes—temple, image, divine glory, high priest, messiah—can somehow come together.

Temple, image, divine glory, high priest, messiah—these can come together. Click To TweetIn John we should not be surprised that, even though this temple-theme has not usually been explored, people have nevertheless seen chapter 17, one of the climactic moments of the whole narrative, as a ‘high-priestly’ prayer.

And just as other themes are fused together, like the varied rainbow colors brought back into the pure white light from which they came, so Jesus turns out to be both the true temple and the true image within that temple and the high priest and, of course, the victorious Messiah.

Remembering the Romans

‘Arms and the man I sing.’ That is the classic Roman ideology, the song of a nation whose vocation was war.

Throughout John’s gospel, but reaching a peak in chapter 12 and then again in 16 and the dialogue with Pilate in John 18 and 19, John presents Jesus as the one who, like David confronting Goliath, is going out to do battle with ‘the ruler of the world.’

Most have taken this as a reference simply to the unseen forces, the dark satanic power that must be dethroned. That is certainly part of it, but I think that John, like other writers of the time, doesn’t make so clear a separation between what we call ‘spiritual’ and what we call ‘political’ powers.

When Jesus says that ‘the ruler of this world is coming,’ (14:30) he seems to mean troops, not demons, though it is the satan entering into Judas that will ‘accuse’ him, that will hand him over (13:2, 27, 18:3).

The theme is stated most clearly in 12:31–32. Some Greeks at the feast have asked to see Jesus, and Jesus appears to regard this as a sign that the last battle is near: if his message is to bear fruit in the wider world, the grain of wheat must fall into the earth and die: the dying fall, perhaps, of the music of love. What is required, for the whole world to be able to receive, and respond in faith to, the news of God’s kingdom, is for the dark power that has kept the whole world in captivity to be overthrown.

John doesn't make so clear a separation ‘spiritual’ and ‘political.’ Click To TweetAn excerpt from the course The Day the Revolution Began. Get your free excerpt HERE.

This is new-Exodus language: Pharaoh must be defeated for the slaves to be freed.

And this will happen through Jesus’ death: ‘Now comes the judgment of this world! Now this world’s ruler is going to be thrown out! And when I’ve been lifted up from the earth, I will draw all people to myself.’

Latest posts by N.T. Wright (see all)

- Sneak Peek: What to Expect When Prof. Wright Comes to Houston - May 11, 2023

- The Music of New Creation: Holy Week Eucharist Reflections from N.T. Wright - April 14, 2022

- Hope Amid the Broken Signposts - February 17, 2021