Learn more about Ethnicity, Justice, and the People of God, releasing February 17, 2022.

Choosing a course image is one of the more dreaded tasks involved in course creation. It’s not a difficult task, necessarily. There are millions of stock images available on the Internet, many of them designed to be used across multiple contexts. So choosing an image is a small task, but one that carries an outsized share of the burden of the course.

You know the cliche. A picture is worth a thousand words. This has its benefits and its drawbacks. A course image is often the first asset our audience sees when encountering a new course, before the description, curriculum, or even title. That image must communicate those thousand words in a split second, and communicate them accurately. How do you encapsulate everything a course is about (and avoid everything it isn’t!) in a single image? Well, it can’t really be done. If it could, we wouldn’t need entire courses. Or books or articles or nuanced discussions of any kind for that matter. But it has to try at least to approximate important concepts.

Course Backdrop

When my colleague, Jennifer Loop, went down to Wheaton, Illinois, to film Prof. McCaulley’s portion of our new course, Ethnicity, Justice, and the People of God, she was faced with a task she had not expected. Filming in a new location required designing a new backdrop; something that would be engaging, but not distracting. (After two years of Zoom meetings, we’re all acutely aware of how important a background is.) Some items were placed on shelves to provide warmth, but we needed that personal touch. Someone suggested adding Prof. McCaulley’s book, Reading While Black, because some of his lecture material expanded on book material. Jennifer happened to have a copy on hand.

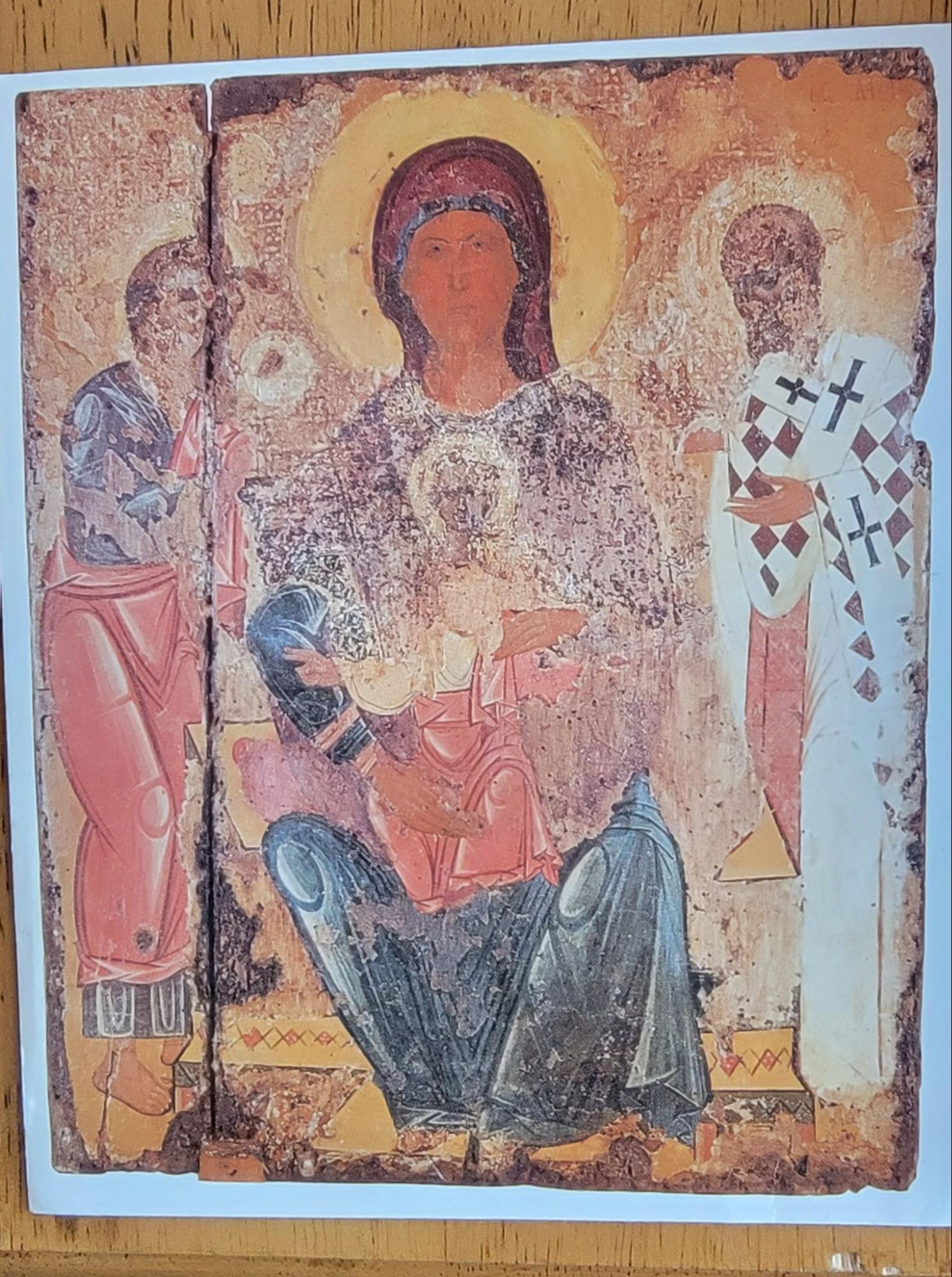

When placing the book, a bookmark she had been using fell out. It was actually a postcard which featured 11th century Cypriot iconography depicting the Virgin and Child, Saint Luke, and Lazarus (shown right). Prof. McCaulley picked up the postcard and commented that he appreciated the image. He decided to add the postcard to the backdrop as well. (If you look closely, you can make out the icon in the right side of the frame, next to a clock.) This interaction provided our first sense of direction in finding an image for the course.

What is an Icon?

There are many less-than-robust images that could be associated with a course on ethnicity, justice, and the Bible. Think ‘Hands Across America’. Think corporate workplace inspirational posters. Think Tommie Smith and John Carlos and the ‘68 Olympics. In many circles, these images have become so cliched as to retain little messaging. On the flip side, one could use an image so hyper-present, so laden with of-the-moment connotation, that deep and inaccurate associations are formed too early.

Fortunately, the Church has a long history of religious art that extends far back beyond smart phones, photography, or Google Image search. Icons are images created specifically for Christian worship, and were heavily used in early and Mediaeval Christianity, and are still integral to many faith practises, especially in the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Some icons in the early church were used for theological education to the illiterate masses, with systems of evocative colour schemes, postures, etc., which all taught theological truths. The imagery of the icon always points to God in one way or another, but also provides an avenue for encountering deeper spiritual truth rather than simply acquiring cognitive information. In revealing a straight-forward truth, the imagery and the encounter itself contain layers of hidden meaning.

Others were used in worship, as an aid to prayer. In the same way that you might fold your hands, bow your head, and close your eyes as signals to your mind and body to ‘enter into prayer’, the icon engages the senses in a specific way and cues our faculties to establish a posture (inwardly and outwardly) towards God in preparation for prayer.

In truth, most icons served both pedagogical and spiritual purposes, since the demarcation between worship and learning is a modern, and largely unhelpful, divide.

In looking to an icon, you’re really looking through it, to see God’s domain. The content signals something about God’s reality. More than that, the religious icon is a moment and a space where the overlap of the earthly and the spiritual is evident. Just as the sacraments of Eucharist and baptism represent moments when the fullness of God’s reality invades our present, the icon offers a visible sign of the invisible reality.

Icons, like the one used for this course, force a different mode of thinking than is typical when we encounter an image. If a picture is worth a thousand words, an icon transcends words. It provides deep theological education, an infrastructure for prayer, a sensory-emotional connection to the worshipping body of the church, and a spiritual portal to the Mysteries of God.

The Feast of All Saints

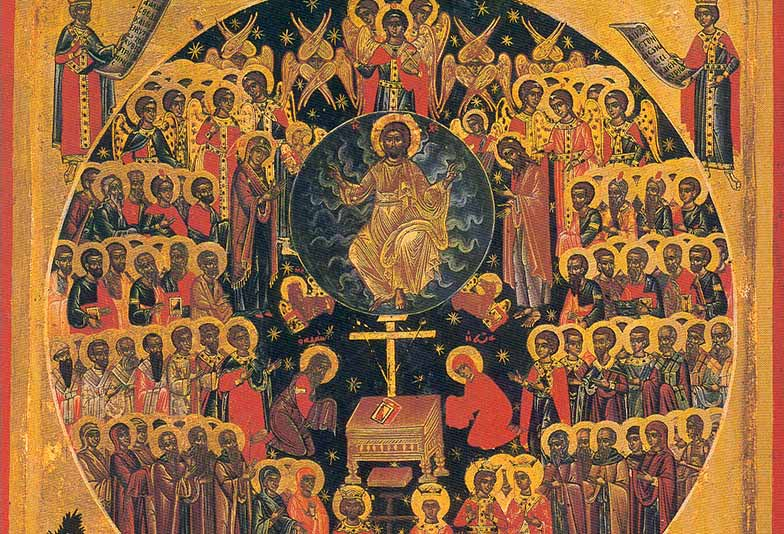

The icon used for our course image is one of many after the same style. Sometimes called The Great Cloud of Witness, it is often used in celebrations of Sunday of All Saints, a day honouring the masses of Christians who are not canonised saints.

The icon is set in Paradise, indicated by the abundant trees often included. The bottom section usually depicts Abraham, Jacob, and the Penitent Thief crucified with Jesus. These together symbolise God’s promises in the Old Testament, most significantly the promise to gather together all the nations of the world in worship of the one true God. At the centre of the icon is Christ, surrounded by a literal visualisation of the ‘great cloud of witness’ described in Hebrews.

Sometimes the individuals are arranged by ‘type’ (martyrs, ascetics, Apostles, priests, etc.) and sometimes notable individuals are recognizable. But I tend to prefer the versions where no one is individually recognisable, and where everyone is mixed together. Many modern versions of the icon depict this explicitly by including believers of a far greater diversity than the art of the 11th century could often achieve. Below are a few more examples of this icon from different regions and time periods.

As Prof. Wright points out, the ancient world didn’t have ethnic separation in the same way as today, with inherent prejudices attached. The icon exemplifies this. Much of the history of religious art attests to this in the same way. It’s easy to look at the recent past and see the ugly history of Christian collusion in efforts to divide God’s people along arbitrary racial and ethnic lines. But I’m encouraged when I look back at the early centuries of Christian thought to see that, (at least in their art if not in their international relations) their depictions of unity and the end of all things holds up before us a benchmark of inclusion many modern churches have yet to achieve.

Spiritual Maximalism and the Scarcity Mindset

Regardless of who is included in the ‘cloud’ or how recognizable, the crucial aspect of the image is that it is painted such that the number of Saints is beyond counting. Their bodies spill out of the visual frame in a way indicating innumerable abundance, again mirroring the Old Testament promises to Abraham of a family more numerous than the stars in the sky. This aesthetic maximalism is important insofar as it crowds the entirety of the frame with imagery and colour. And not just any imagery, but human beings, of all different ehtnicities.

More than just the multitude of God’s family, the icon indicates the unity of God’s family. The company of saints with Christ is encompassed in a circle of light, called a mandorla in iconography. The mandorla is a common iconographic element symbolising both visible light and the glory of Christ that exists beyond the visible. But in this case, it also serves to show that those within its orbit share communion with God and with each other. Very often mandorlas are almond-shaped (that’s where the word comes from, Italian for almond), but in All Saints the circle is apt, as it shows the perfection of God’s family (in the sense of unbrokenness), but also includes the potential of eternal expansion while retaining the same shape.

There is no humanly defined boundary. It extends eternally. One of the pernicious and underappreciated difficulties to achieving justice and equity is the pervasiveness of a scarcity mindset. For many people, this mindset subconsciously says that someone else’s freedom portends (directly or indirectly) my own bondage; that there’s only so much freedom to go around. Or that unity in God’s kingdom requires all individual and cultural particularities to be subsumed beneath a dominant cultural ‘type’. On the contrary, as both Prof. McCaulley and Prof. Wright assert, Christ is not the destroyer of cultures; he is the redeemer of cultures.

Especially in the Western Church, one of the pressing tasks is to undercut in our own thinking the assumptions of White normativity in Christianity. The reality is, today and historically, there have been more non-white Christians globally than white Christians. And the way of being Christian does not have to be, nor has it always been, directed by Whiteness. To put it boldly, the tribalism of humanity in general, the church in particular, and the American church especially, is something that is hated by God. Any undermining of that tribalism, which icons like All Saints do in the visual medium, is a spiritual good. God loves all peoples (individually and culturally) of all tribes, nations, and tongues. We aim to articulate and celebrate that.

Learn more about Ethnicity, Justice and the People of God, releasing February 17, 2022.

Ryan Liguori

Latest posts by Ryan Liguori (see all)

- Why Don’t the Gospels Match? - September 29, 2022

- How to Make the Most of an N.T. Wright Online Course - June 7, 2022

- Three Key Concepts from Prof. Wright’s New Course An Advanced Study in Galatians - May 19, 2022